Buddhism started as early as 4th or 6th BCE when Siddharta Gautama began to spread his teachings of suffering, nirvana, and rebirth in India. Siddharta himself was averse to accepting images of himself and used many different symbols to illustrate his teachings. There are eight different auspicious symbols of Buddhism, and many say that these represent the gifts that God made to Buddha when he achieved enlightenment.

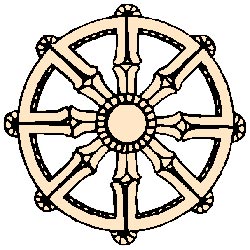

The role of the image in Early Buddhism is not known, although many surviving images can be found because their symbolic or representative nature was not clearly explained in early texts. Among the earliest and most common symbols of Buddhism are the stupa, Dharma wheel, and the lotus flower. The dharma wheel, traditionally represented with eight spokes, can have a variety of meanings. It initially only meant royalty (a concept of the “Monarch of the Wheel, or Chakravatin), but it started to be used in a Buddhist context on the Pillars of Ashoka during the 3rd century BC. The Dharma wheel is generally seen as referring to the historical process of teaching the buddhadharma; the eight spokes refer to the Noble Eightfold Path. The lotus, as well, can have several meanings, often referring to the inherently pure potential of the mind.

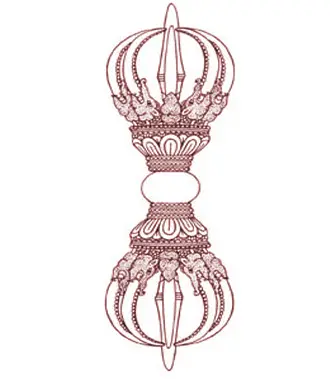

Other early symbols include the Trisula, a symbol used since around the 2nd century BC that combines the lotus, the vajra diamond rod and the symbolization of the three jewels (The Buddha, the dharma, the sangha). The swastika was traditionally used in India by Buddhists and Hindus as a good luck sign. In East Asia, the Swastika is often used as a general symbol of Buddhism. Swastikas used in this context can either be left or right-facing.

Early Buddhism did not portray the Buddha himself and may have been aniconic. The first hint of human representation in Buddhist symbolism appears with the Buddha’s footprint.

The parasol or umbrella

The two golden fish

The Conch shell

The Lotus Flower

The Banner of Victory

The vase

|

A vase can be filled with many different things. The vase, in Buddhism, can mean the showering of health, wealth, prosperity and all the good things that come with enlightenment. |

The Dharma wheel

The eternal knot

The Bodhi Tree, also known as Bo (from the Sinhalese Bo), was a large and very old Sacred Fig tree located in Bodh Gaya (about 100 km from Patna in the Indian state of Bihar), under which Siddhartha Gautama, the spiritual teacher and founder of Buddhism later known as Gautama Buddha, is said to have achieved enlightenment, or Bodhi. In religious iconography, the Bodhi tree is recognizable by its heart-shaped leaves, which are usually prominently displayed. It takes 100 to 3,000 years for a bodhi tree to fully grow.The term “Bodhi Tree” is also widely applied to currently existing trees, particularly the Sacred Fig growing at the Mahabodhi Temple, which is a direct descendant of the original specimen. This tree is a frequent destination for pilgrims, being the most important of the four main Buddhist pilgrimage sites. Other holy Bodhi trees which have great significance in the history of Buddhism are the Anandabodhi tree in Sravasti and the Bodhi tree in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Both are believed to have been propagated from the original Bodhi tree. The Bodhi Tree, also known as Bo (from the Sinhalese Bo), was a large and very old Sacred Fig tree located in Bodh Gaya (about 100 km from Patna in the Indian state of Bihar), under which Siddhartha Gautama, the spiritual teacher and founder of Buddhism later known as Gautama Buddha, is said to have achieved enlightenment, or Bodhi. In religious iconography, the Bodhi tree is recognizable by its heart-shaped leaves, which are usually prominently displayed. It takes 100 to 3,000 years for a bodhi tree to fully grow.The term “Bodhi Tree” is also widely applied to currently existing trees, particularly the Sacred Fig growing at the Mahabodhi Temple, which is a direct descendant of the original specimen. This tree is a frequent destination for pilgrims, being the most important of the four main Buddhist pilgrimage sites. Other holy Bodhi trees which have great significance in the history of Buddhism are the Anandabodhi tree in Sravasti and the Bodhi tree in Anuradhapura, Sri Lanka. Both are believed to have been propagated from the original Bodhi tree. |

The footprint of the Buddha is an imprint of Gautama Buddha’s one or both feet. There are two forms: natural, as found in stone or rock, and those made artificially. Many of the “natural” ones, of course, are acknowledged not to be actual footprints of the Buddha, but replicas or representations of them, which can be considered Cetiya (Buddhist relics) and also an early aniconic and symbolic representation of the Buddha. The footprints of the Buddha abound throughout Asia, dating from various periods. They often bear distinguishing marks, such as a Dharmachakra at the center of the sole or the 32, 108 or 132 auspicious signs of the Buddha, engraved or painted on the sole. The footprint of the Buddha is an imprint of Gautama Buddha’s one or both feet. There are two forms: natural, as found in stone or rock, and those made artificially. Many of the “natural” ones, of course, are acknowledged not to be actual footprints of the Buddha, but replicas or representations of them, which can be considered Cetiya (Buddhist relics) and also an early aniconic and symbolic representation of the Buddha. The footprints of the Buddha abound throughout Asia, dating from various periods. They often bear distinguishing marks, such as a Dharmachakra at the center of the sole or the 32, 108 or 132 auspicious signs of the Buddha, engraved or painted on the sole. |

An Empty Throne lies in the concept of ’empty,’ an important element of mysticism. This symbol was also symbolizing the royalty of Siddharta Gautama. An Empty Throne lies in the concept of ’empty,’ an important element of mysticism. This symbol was also symbolizing the royalty of Siddharta Gautama. |

Begging Bowl The begging bowl is the simplest but one of the most important objects in the daily lives of Buddhist monks. The begging bowl has been the primary symbol of the chosen life of the Buddhist monk. Begging Bowl The begging bowl is the simplest but one of the most important objects in the daily lives of Buddhist monks. The begging bowl has been the primary symbol of the chosen life of the Buddhist monk. |

The Lion – is one of Buddhism’s most important symbols. The lion is the symbol of royalty that symbolized what the Buddha was a part of before attaining enlightenment. It is also the power of the Buddha’s teaching and is quite often compared with the roar of a lion. The Lion – is one of Buddhism’s most important symbols. The lion is the symbol of royalty that symbolized what the Buddha was a part of before attaining enlightenment. It is also the power of the Buddha’s teaching and is quite often compared with the roar of a lion. |

The Eight Auspicious Symbols – or (Ashtamangala) are a sacred suite of Eight Auspicious Signs endemic to a number of Dharmic Traditions such as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. The symbols or ‘symbolic attributes’ are yidam and teaching tools. Not only do these attributes, these energetic signatures, point to qualities of enlightened mindstream, but they are the investiture that ornaments these enlightened ‘qualities.’ Many cultural enumerations and variations of the Ashtamangala are extant. Groupings of eight auspicious symbols were originally used in India at ceremonies such as the inauguration or coronation of a king. An early grouping of symbols included a throne, swastika, handprint, hooked knot, a vase of jewels, a water libation flask, a pair of fishes, and a lidded bowl. In Buddhism, these eight symbols of good fortune represent the offerings made by the gods to Shakyamuni Buddha immediately after he gained enlightenment.The Umbrella or parasol (chhatra) embodies notions of wealth or royalty, for one had to be rich enough to possess such an item and, further, to have someone carry it. It points to the “royal ease” and power experienced in the Buddhist life of detachment. The Eight Auspicious Symbols – or (Ashtamangala) are a sacred suite of Eight Auspicious Signs endemic to a number of Dharmic Traditions such as Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Sikhism. The symbols or ‘symbolic attributes’ are yidam and teaching tools. Not only do these attributes, these energetic signatures, point to qualities of enlightened mindstream, but they are the investiture that ornaments these enlightened ‘qualities.’ Many cultural enumerations and variations of the Ashtamangala are extant. Groupings of eight auspicious symbols were originally used in India at ceremonies such as the inauguration or coronation of a king. An early grouping of symbols included a throne, swastika, handprint, hooked knot, a vase of jewels, a water libation flask, a pair of fishes, and a lidded bowl. In Buddhism, these eight symbols of good fortune represent the offerings made by the gods to Shakyamuni Buddha immediately after he gained enlightenment.The Umbrella or parasol (chhatra) embodies notions of wealth or royalty, for one had to be rich enough to possess such an item and, further, to have someone carry it. It points to the “royal ease” and power experienced in the Buddhist life of detachment.

The two fishes originally represented India’s two main sacred rivers – the Ganges and Yamuna. These rivers are associated with the lunar and solar channels originating in the nostrils and carrying the alternating rhythms of breath or prana. They have religious significance in Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist traditions but also in Christianity (the sign of the fish, the feeding of the five thousand). In Buddhism, the fish symbolize happiness as they have complete freedom of movement in the water. They represent fertility and abundance. Often drawn in the form of carp, which are regarded in the Orient as sacred on account of their elegant beauty, size, and life span. The treasure vase or Urn of Wisdom represents health, longevity, wealth, prosperity, wisdom and the phenomenon of space. The lotus flower, representing the ‘primordial purity’ of the body, speech, and mind, floating above the muddy waters of attachment and desire, represents the full blossoming of wholesome deeds in blissful liberation. Conch – The right-turning white conch shell represents the beautiful, deep, melodious, interpenetrating and pervasive sound of the Buddhadharma, which awakens disciples from the deep slumber of ignorance and urges them to accomplish their welfare and the welfare of others. The Knot – The ‘endless knot’ or ‘eternal knot’ represents the intertwining of wisdom and compassion; it represents the mutual dependence of religious doctrine and secular affairs. Victory Banner – Dhvaja banner was a military standard of ancient Indian warfare. Makara Dhvaja has become latter an emblem of the Vedic god of love and desire – Kamadeva. Within the Tibetan tradition, a list of eleven different forms of the victory banner is given to represent eleven specific methods for overcoming defilements. Many variations of the Dhvaja design can be seen on the roofs of Tibetan monasteries to symbolize the Buddha’s victory over four maras. The Dharma-Wheel (Dharmachakra) – The Wheel of Law, sometimes representing Sakyamuni Buddha and the Dharma teaching; also representing the mandala and chakra. This symbol is commonly used by Tibetan Buddhists, and it sometimes also includes an inner wheel of the Gankyil (Tibetan). |

Swastika – In the Buddhist tradition, the swastika symbolizes the feet or footprints of the Buddha and is often used to mark the beginning of texts. Modern Tibetan Buddhism uses it as a clothing decoration. With the spread of Buddhism, it has passed into the iconography of China and Japan, where it has been used to denote plurality, abundance, prosperity and long life. Swastika – In the Buddhist tradition, the swastika symbolizes the feet or footprints of the Buddha and is often used to mark the beginning of texts. Modern Tibetan Buddhism uses it as a clothing decoration. With the spread of Buddhism, it has passed into the iconography of China and Japan, where it has been used to denote plurality, abundance, prosperity and long life. |

Four Guardian Kings – In the Buddhist faith, the Four Heavenly Kings are four guardian gods, each of whom watches over one cardinal direction of the world. Four Guardian Kings – In the Buddhist faith, the Four Heavenly Kings are four guardian gods, each of whom watches over one cardinal direction of the world. |

Buddha Eyes – Also called Wisdom Eyes, this pair of eyes can usually be found depicted on all four sides of the Buddhist shrines known as Stupas. The symbol denotes the all-seeing and omniscient eyes of Buddha and is representative of the Lord’s presence all around. The curly line below the eyes in the middle (where the nose is on a face) is the Sanskrit numeral one that symbolizes the unity of everything and also signifies that the only way to attain enlightenment is through Buddha’s teachings. The dot between the eyes is indicative of the third eye, which represents spiritual awakening. Buddha Eyes – Also called Wisdom Eyes, this pair of eyes can usually be found depicted on all four sides of the Buddhist shrines known as Stupas. The symbol denotes the all-seeing and omniscient eyes of Buddha and is representative of the Lord’s presence all around. The curly line below the eyes in the middle (where the nose is on a face) is the Sanskrit numeral one that symbolizes the unity of everything and also signifies that the only way to attain enlightenment is through Buddha’s teachings. The dot between the eyes is indicative of the third eye, which represents spiritual awakening. |

Vajra -The Vajra is a Buddhist tantric symbol representative of great spiritual power and firmness of spirit. It symbolizes one of the three main branches of Buddhism, Vajrayana. Shaped like as club having ribbed spherical heads, the Vajra is symbolic of the attributes of a diamond (purity and indestructibility) as well as the properties of a thunderbolt (irresistible energy). It also represents endless creativity, skillful activity, and potency. In Tibetan Buddhism, the Vajra is also a ritual tool and is known as Dorje. It is used along with a bell by lamas and other practitioners of sadhana. Vajra -The Vajra is a Buddhist tantric symbol representative of great spiritual power and firmness of spirit. It symbolizes one of the three main branches of Buddhism, Vajrayana. Shaped like as club having ribbed spherical heads, the Vajra is symbolic of the attributes of a diamond (purity and indestructibility) as well as the properties of a thunderbolt (irresistible energy). It also represents endless creativity, skillful activity, and potency. In Tibetan Buddhism, the Vajra is also a ritual tool and is known as Dorje. It is used along with a bell by lamas and other practitioners of sadhana. |